Washington eviction law has changed a lot in recent years. Be careful about trusting other eviction information on the internet, as much of it is outdated, incomplete, or otherwise inaccurate.

Please also note that this article is very technical (i.e., boring). Unfortunately, there’s no way to make this information interesting without glossing over important steps. It’s critical for landlords and property managers to get every step right or the eviction will take much longer and cost much more money.

In this article, we discuss the following:

- Overview of the residential eviction process from start to finish

- Approximate timeline for an eviction in Washington State

Wait, before reading further, make sure this article addresses your situation!

Please note this article is about evictions under the Washington Residential Landlord-Tenant Act. Commercial evictions are exempt from this law. Additionally, this law doesn’t apply to certain living arrangements, such as:

- short-term residents of hotels and motels,

- care facilities and certain group homes,

- employment-based housing, and

- (arguably) illegal squatters/trespassers

If you’re concerned your resident may not be a “tenant” under the law, then check out our article on how to eject a non-tenant resident from an exempt living arrangement.

Please also note that some jurisdictions, like Seattle and Tacoma, impose additional tenant protections that make the eviction process more complicated and time-consuming. The information in this article still applies to tenancies in those jurisdictions, but you’ll need to check out our companion articles on Seattle and Tacoma evictions as well.

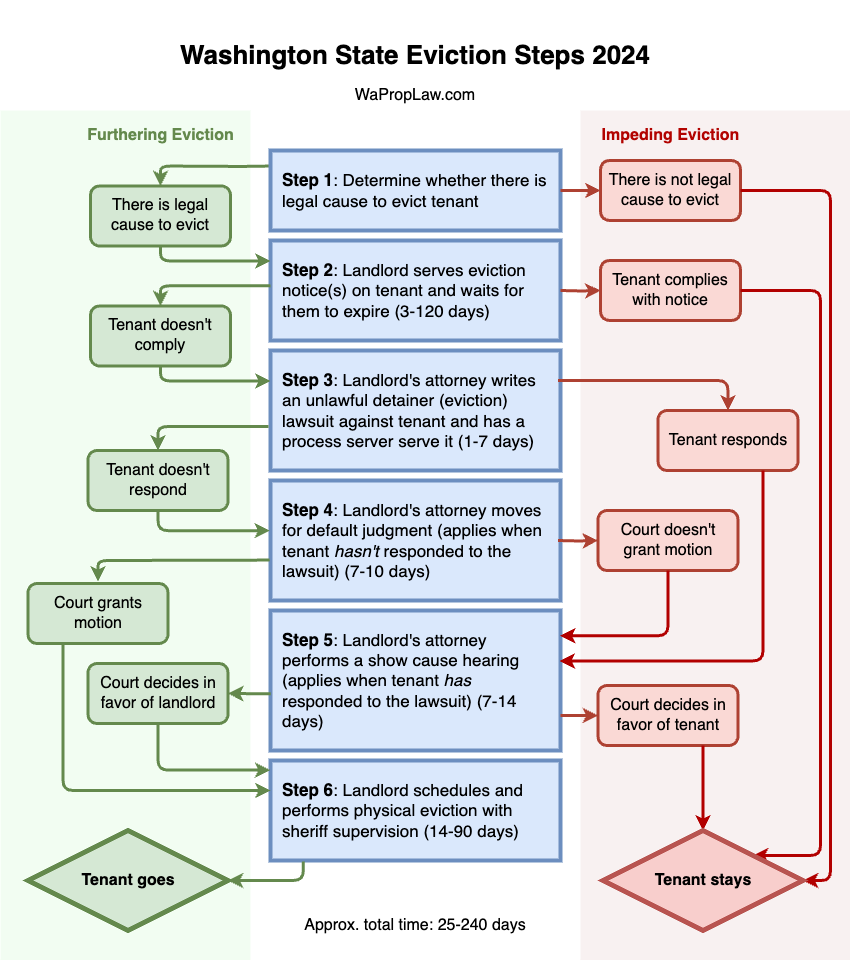

The Washington State eviction process from start to finish

In this section, we outline the Washington eviction process step-by-step. Please keep in mind that this is merely an overview of the typical eviction process. Many things can go wrong during the process, some of which we’ve outlined in our article addressing common issues that arise during evictions. Due to the costs and expense of evicting a tenant, you may want to consider alternatives, such as offering your tenant cash for keys.

Step 1: Your tenant becomes eligible for an eviction.

Landlords can’t just evict the tenant for any reason you want. Under Washington law, there are only 17 causes for evicting a residential tenant. We go into all 17 causes in a separate article, but the five below are most common:

- Nonpayment: The tenant is late on their rent

Notice type: 14-day pay or vacate (specific form required by RCW 59.18.057).

Tip: A 14-day notice to pay or vacate is the only notice with a statutorily-required form. The Washington State Attorney General has created a version of the 14-day notice available here. - Breach: Tenant is violating their lease or residential landlord-tenant law

Notice type: 10-day comply or vacate.

Tip: You must specifically identify “the acts or omissions constituting the breach” and state explicitly that the rental agreement will end if your tenant doesn’t comply. - Nuisance or waste: The tenant is causing serious disturbances to neighbors or damaging the premises

Notice type: 3-day notice to vacate

Tip: Waste is when your tenant causes “substantial injury” to the premises. Nuisance is when your tenant causes “substantial discomfort” to neighbors. A court will not usually find waste or nuisance for minor breaches. - You want to sell: You wish to evict a tenant to sell a single-family residence (condominium is fine, but duplex or larger not allowed).

Notice type: 90-day notice to vacate

Tip: Landlord must make “reasonable attempts to sell” the premises, including, at a minimum, listing the house for sale for a “reasonable price” within 30 days of the tenant vacating the unit. - You want to occupy: Landlord or immediate family intend to occupy the premises

Notice type: 90-day notice to vacate

Tip: Applies when the landlord or their immediate family want to occupy the unit and there are no similar units vacant in the same building. - Nonpayment: The tenant is late on their rent

Notice type: 14-day pay or vacate (specific form required by RCW 59.18.057)

Tip: Leases commonly provide for a 3-5-day grace period after the first of the month. Nonpayment notices cannot be issued during this period.

Step 2: Serve eviction notices and wait for them to expire

Highly experienced landlords typically fill out and serve the eviction notices themselves. However, if you’ve never filled out an eviction notice yourself, you may want to hire an experienced landlord-tenant attorney at this stage to draft your notices and coach you through the process. An attorney can also have their process server serve the notices for you.

If you plan to serve the notices yourself, you need to fill out a lawful notice form. Just about every cause for eviction will require a different form (i.e., nonpayment requires a different form than 10-day comply or vacate). We strongly recommend the forms provided by RHAWA. Do not just use a random form you found online

Usually, you should serve a separate notice for each reason to evict. For example, if your tenant is late on their rent and violating a rule in the lease, you’d want to serve both a ’14-day notice to pay or vacate’ for nonpayment and a ’10-day notice to comply or vacate’ for breaching the lease. However, don’t serve notices that don’t apply because doing so may confuse the tenant and legally invalidate all your notices.

The waiting periods for these notices range from as little as three days (for waste or nuisance) to as long as 120 days (for substantial renovations). If you serve the wrong notices or fail to include required information, you will need to re-serve the notices and restart the waiting period. Therefore, when serving longer notices, it’s very important to use the correct forms to avoid wasting time (another reasons you may want to hire an attorney to prepare longer notices).

As for service, you must strictly adhere to the following statutory process:

- Personal service: Knock on the door and try to personally hand the notice to the tenant (i.e., personal service). If (and only if) that fails, then

- Substitute personal service: Hand the notice to another resident at the premises of suitable age and discretion (at least 15 years old, ideally 18+). If (and only if) that fails, then

- Posting and mailing: By taping a copy of the notice on the door and mailing a copy to the residence by First Class USPS with “certificate of mailing” for proof. It’s best to take a photo of the notice posted on the door for proof.

Once you’ve successfully served all the applicable notices on your tenant, the notice waiting period begins. If you’ve served more than one notice with varying notice periods (e.g., a 3-day notice for waste or nuisance and a 14-day nonpayment notice) then you will usually want to wait for all notice periods to elapse before proceeding (e.g., 14 days).

Step 3: Start an unlawful detainer lawsuit against your tenant

This is the part of the process where it’s almost impossible to proceed without hiring an attorney.

If your tenant fails to comply with the notice by the end of the waiting period, the next step is starting a lawsuit to obtain a court order restoring you to possession of the premises. Unfortunately, a lawsuit is the only legal way. You cannot lawfully lock the tenant out or engage in other self-help remedies (though breaking the law is becoming an increasingly tempting option).

Eviction lawsuits are brought using an “unlawful detainer” cause of action. The term “unlawful detainer” means you are alleging the tenant is illegally keeping custody of the unit. The first step in starting an unlawful detainer lawsuit is to draft the summons and complaint. The summons is a specialized form provided by statute. The complaint alleges the unique facts entitling the landlord to a writ of restitution (which orders to sheriff to help the landlord retake the unit) and a judgment for damages, fees, and costs. Sometimes, the complaint only needs to be a couple pages long, other times it needs to be much longer. In certain cases, it is also necessary to prepare separate sworn declarations from the landlord, neighbors, or other tenants. For the sake of efficiency, it’s often best to prepare these declarations alongside the complaint.

Once the summons, complaint, and associated documents (if any) are drafted, these papers must be served on the tenant. Service of the summons and complaint must be performed by someone other than the landlord, so usually it’s best to hire a professional process server. However, not all professional process servers have experience with the unique service procedures applicable to landlord-tenant matters, so that is something to keep in mind.

Step 4: Move for a default judgment?

A “default judgment” is an win by default in favor of a landlord that occurs when the tenant fails to “appear” in response to a summons.

What does a failure to “appear” look like? Once the summons and complaint are served, the tenant has between 7-30 days to “appear.” Not every response from a tenant constitutes an “appearance.” A tenant’s “appearance” does not need to be formal. However, a tenant’s response must be in “substantial compliance” with RCW 4.28.210 and CR 4(3), which require that an appearance must be “in writing, shall be signed by the defendant or the defendant’s attorney, and shall be served upon the person whose name is signed on the summons.” Mere pre-litigation communications (phone calls, text messages, etc.) are insufficient to constitute an appearance.

If your tenant does not “appear” in response to the summons, then the most efficient strategy is to file a motion for default judgment, which will entitle the sheriff to schedule a physical eviction.

However, relying on a default judgment is a gamble because default judgments are fragile. If the tenant gets an attorney free attorney after the default judgment but before the physical eviction, the tenant’s attorney can move the court without notice to your attorney (i.e., “ex parte”) to stop (i.e., “stay”) execution of the default judgment until the court holds a show cause hearing. Courts grant these motions automatically. Therefore, by relying on a default judgment, you’re essentially betting that the tenant won’t find a lawyer at the last minute.

If your bet pays off, you’ve saved several days and the cost of paying your attorney to perform a show cause hearing. However, if your bet doesn’t pay off, then you’ve lost several weeks or months and you’ll have to pay the sheriff twice to schedule the physical eviction. Therefore, it may be better to simply do a show causing hearing at the outset rather than bother with a default judgment. We explain in more detail below:

Obtaining a default judgment can take as little as around eight days. The landlord’s attorney will then send the default judgment to the sheriff for scheduling of the physical eviction. Unfortunately, it often takes the sheriff two months or more to physically evict the tenant (depending on your jurisdiction), which leaves a lot of time for the tenant to stop execution of the default judgment (as explained above). If the tenant stops execution , the sheriff will cancel the physical eviction date. The landlord’s attorney will then schedule a show cause hearing and, upon succeeding at the show cause hearing, send the new judgment to the sheriff for execution. Unfortunately, the new physical eviction goes back to the end of the line for another two month wait. Thus, a landlord could end up waiting eight days for a default judgment, 60 days for a physical eviction that’s cancelled at the last minute, seven days for a show cause hearing, and another 60 days for the second physical eviction for a total of around 135 days (4.5 months). A landlord could avoid wasting 70 days by proceeding straight to a show cause hearing. The downside of proceeding with a show cause hearing is that the landlord’s attorneys fees will be higher because they will need to pay their attorney for a court appearance.

One last thing to note: Courts cannot award attorneys fees on a default judgment, but there is no prohibition against requesting costs or damages. Practically speaking, tenants rarely actually pay these judgments so it doesn’t matter much either way.

Step 5: Show Cause hearing?

If your tenant answered the summons and complaint, or successfully stopped execution of the default judgment, then the next step is to move for a show cause hearing seeking the relief requested in the complaint (a writ of restitution entitling you to retake possession and judgment for damages, fees, and costs). After a landlord has alleged facts sufficient to evict a tenant in the complaint, the show cause hearing allows the tenant to “show cause” why the court shouldn’t evict them. The show cause hearing must be set 7-30 days from the date of notice to the tenant.

It doesn’t take much for a tenant to succeed at this stage. Washington courts have ruled that “[a] tenant’s testimony specifically disputing the breach of the lease alleged by the landlord creates issues of material fact warranting trial.” Therefore, a tenant can sometimes lie their way to victory at the show cause stage if the landlord is attempting to prove disputable facts. Evictions not based on disputable facts (e.g., the landlord’s wish to renovate the premises) are less likely to be defeated at the show cause stage.

In most cases, landlords prevail at the show cause hearing stage. When successful, the court will grant the landlord a writ of restitution, and usually also a money judgment for delinquent rent, costs, and reasonable attorney’s fees.

In the event a landlord doesn’t prevail at the show cause hearing, the next steps are either a motion for reconsideration to the same court commissioner or a motion for revision before a Superior Court judge (or both). If unsuccessful there, the next step is a civil trial. Usually, if you end up at this stage, you’ve done something wrong and it’s better to start again at the beginning with new notices.

Step 6: Deliver the writ of restitution to the Sheriff’s office for posting and physical eviction

Assuming the landlord prevails either at a default judgment or at a show cause hearing, the next step is to deliver the writ of restitution (the court document ordering the sheriff to help you regain possession) to the sheriff’s office for posting and execution.

Theoretically, this part could take as little as four days. The sheriff could post the writ the day after it’s issued by the court and then wait the minimum three days to physical evict the tenant. However in practice, it usually takes 2-12 weeks due to understaffing. The exact time will vary by jurisdiction and backlog.

First, a deputy must post the writ on the tenant’s door. Just scheduling a deputy to post the writ usually takes 1-2 weeks in Pierce County. Then the tenant has five days to vacate. If the tenant fails to vacate, the landlord must call the sheriff back and schedule a physical eviction. This usually takes another 1-3 weeks in Pierce County.

If the tenant still hasn’t vacated by the scheduled physical eviction, you’ll need to move the tenant’s personal belongings to the nearest public right-of-way or into storage. Storage is required if the tenant has expressly requested it within three days after service of the writ. Importantly, the sheriff won’t actually help your tenant move out. They’re just there to “keep the peace” while you, or a mover, does the hard work.

That’s the end of the process! Simple right? 🙄

Approximate eviction timeline

Evictions in Washington are a long, complex, and (in some cases) uncertain process. Evictions usually take between 2-4 months, but they can take substantially more or less time depending on how the tenant responds and staffing at your local sheriff’s department. This section compares an eviction where everything goes just right to an eviction where several things go wrong. Hopefully this helps provide some idea of why some evictions take longer than others.

Timeline of a fantasy world, best-case scenario nonpayment eviction

Here is the timeline for a nonpayment eviction if everything goes as fast as legally possible. Again, this is the theoretical best-case scenario. In this timeline, the nonpayment eviction takes about a month.

Day 0: Tenant fails to make a payment

Day 1: Landlord serves a 14-day notice to pay or vacate

Day 15: The tenant doesn’t comply within 14 days. The landlord has already contacted an attorney who has already drafted the summons and complaint.

Day 16: The landlord’s process server successfully serves the summons and complaint on the tenant the next day. Because the summons is served personally, the response date is seven days out.

Day 23: The tenant doesn’t appear by the response date on the summons, so the landlord’s attorney moves for and obtains from the court a default judgment against the tenant, which is granted the same day. The landlord delivers the writ of restitution to the Sheriff’s office for posting.

Day 24: The Sheriff posts the writ of restitution on the tenants’ door the day after the writ is issued.

Day 28: The Sheriff supervises the physical eviction and the tenant is gone for good.

Timeline of a more normal nonpayment eviction

Below is the timeline for a realistic nonpayment eviction. In total, this nonpayment eviction took around three months.

Day 0: Tenant fails to make a payment

Day 5: Landlord serves a 14-day notice to pay or vacate

Day 19: The tenant doesn’t comply with the 14-day notice to pay or vacate so the landlord contacts an attorney who begins drafting the summons and complaint.

Day 25: Attorney finishes drafting the summons and complaint and sends them out to the process server for service.

Day 27: The landlord’s process server is unable to personally serve the summons and complaint because the tenant is evading service, so they post and mail the summons and complaint instead. This requires a nine-day response deadline.

Day 37: The tenant fails to respond by the deadline on the summons, so the landlord’s attorney files the complaint and moves for a default judgment.

Day 39: The court grants the default judgment. It takes two days due to a backlog of cases, a weekend, or holiday. The landlord sends the writ of restitution to the sheriff’s office for execution.

Day 53: The Sheriff is backlogged, so it takes two weeks for them to posts the writ of restitution on the tenants’ door.

Day 56: The tenant doesn’t respond to the writ of restitution within three days, so the landlord’s attorney calls the sheriff to schedule the physical eviction, which takes another two weeks due to the backlog (scheduled for day 70).

Day 68: The tenant finally gets around to defending themselves. They call the number on the nonpayment form and get a free attorney who moves for an ex parte stay of the writ of restitution at the last minute, which the court grants. The Court sets a show cause hearing for the following week.

Day 78: The landlord’s lawyer argues successfully at the show cause hearing, so the court lifts the stay of the writ of restitution.

Day 92: The Sheriff reschedules the physical eviction, again two weeks out due to the backlog.

In sum, evictions in Washington often take between 2-8 months (depending on the initial eviction notice).