An easement is a non-possessory interest in real property that allows one or more person to use a piece of property for a specific purpose, even though they don’t own the property. If this seems confusing, you are not alone. In this article, we will walk you through the most common types of easements, how they originate, and how you can deal with common easement disputes that arise in your land use.

Why is this information important? Because easements tend to impact the value and usefulness of the property they burden, and add value to the property they benefit. If your property is burdened by an easement, the easement may complicate and hinder the uses to which you can put your property. Alternatively, if you or your property is benefited by an easement, that may expand the potential uses of your property and make it more valuable.

Types of Easements

Washington law sets out two main kinds of easement:

Easements in gross – These easements give benefits to specific parties, regardless of what property they own. The party that benefits from an easement in gross usually cannot transfer those rights to another party.

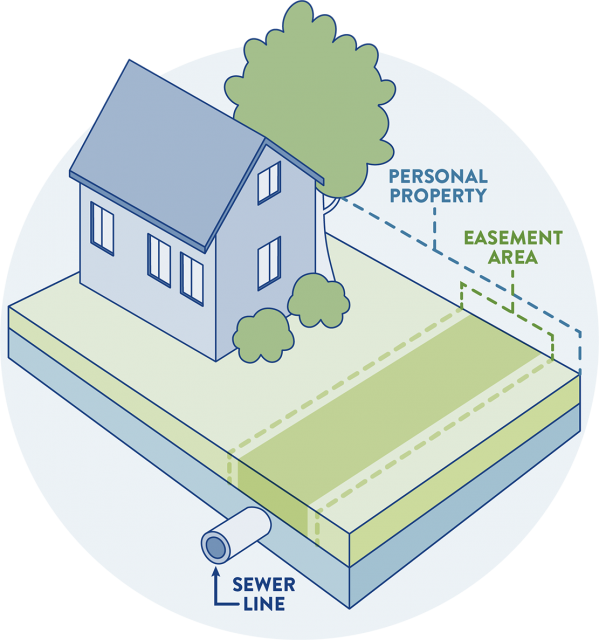

This kind of easement is common when, for example, a utility company wants to install power lines or gas lines on a property. That specific utility company owns the easement and often cannot transfer its easement rights to anyone else.

Easements appurtenant – Instead of benefiting a specific person, this kind of easement “runs with the land” and therefore benefits whoever owns a particular property. In other words, this kind of easement is inseparable from the subject property, and passes from one owner to the next as the property is transferred unless something operates to extinguish the easement.

A common example is a driveway easement. An easement appurtenant can occur when Neighbor A has no other way to access his land by vehicle except via Neighbor B’s existing driveway. B can grant A an easement appurtenant allowing A to use B’s driveway. If A ever sells the property, the new owner will inherit the right to use B’s driveway. This kind of easement is far more common in the cases we deal with.

Both kinds of easements have legal implications that property owners should carefully consider before granting them. In some cases, easements may arise even without your knowledge, so it is important to learn about any existing easements and what they mean for you.

How Easements Arise?

In some cases, another party may simply request that you grant an easement, giving you the opportunity to agree or not. In other situations, an easement can arise without your express knowledge or consent. Therefore, it is important to be vigilant when you allow others to use your property.

The following easements may exist in your area:

- Express easements – These easements are created by express agreement, and they are the most common. They are typically negotiated by the parties, and then signed into existence by written agreement or by deed. These are the most common and straightforward kinds of easements.

- Easements implied by necessity – An easement by necessity can arise if one property has no access to something absolutely necessary for the use and enjoyment of the property. A common example occurs when one property is landlocked by another, and the owner of the landlocked property needs to pass through part of another’s property to access a public roadway or utility.

- Prescriptive easements – To obtain a prescriptive easement in Washington, one property owner must openly, hostilely, and continuously use part of another’s land for 10 years without permission. The laws for establishing a prescriptive easement are almost the same as the requirements for establishing adverse possession.

- Easements created through eminent domain – Another common way an easement can originate is through eminent domain, which is also commonly referred to as condemnation. The government or an affiliated party (such as a utility company) may use its constitutional powers to take part of your land for the “benefit of the public.” Even if you do not wish to agree to the easement, eminent domain allows the government to take your land as long as it provides “just compensation” to you for the easement. If someone has approached you about a possible eminent domain action, you should speak with a real estate lawyer as soon as you can, and before you sign anything.

- Easements implied by prior use – Easements implied by prior use is the law’s way of honoring informal easement-like arrangements that were likely intended to run with the land. Easements arising from prior use must generally satisfy each of the following elements: (1) One larger property has been subdivided, and some part of the original undivided property has been transferred; (2) Prior to the sale, the owner of the original undivided property had been using one of the now-subdivided lots to benefit another now-subdivided lot; (3) The prior use was reasonably necessary to the enjoyment of the benefited land (a lower bar than easements implied by necessity above); (4) The prior use was continuous up until the time of transfer; and (5) The prior use was reasonably apparent to the parties at time of transfer.

Easement Disputes and Litigation

Once an easement exists—or one party asserts that an easement exists—disputes may arise regarding the easement. Possible issues include:

- Property owners deny the existence of an easement and attempt to stop another party from using their land.

- Property owners try to block the legitimate use of their land under a valid easement.

- Two property owners cannot agree on the specific terms of an easement.

Challenging an Easement or the Way Your Property is Being Used

If you own a piece of property that is subject to an easement and have issues with the way that your land is being used by the easement holder, you may be able to take steps to either remove the easement or limit the way the easement holder uses your land. Some of the remedies available to people who own property that is subject to an easement include the following:

- The issuance of a court order restricting the way that the party with easement rights uses the land.

- Monetary damages for any losses that you experience due to the easement or the use of the land.

- A removal of the easement in its entirety.

Alternatively, if your property is benefited by an easement and the servient (non-benefited) property owner is interfering with your easement rights, you may be able to pursue the following:

- Enforcement of your easement rights.

- Monetary damages for any losses you have suffered as a result of the servient property owner’s erroneous restriction of your use of the easement.